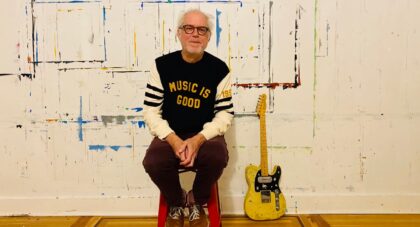

Singer-songwriter Bill Fay has enjoyed a long and legendary career in obscurity. The British musician first raised eyebrows among listeners back in 1970 with his startlingly unique, baroque debut record Bill Fay, which despite a poor commercial impact quickly became a cult classic and garnered comparisons to other unusual and uncelebrated songwriters, such as Nick Drake and Alexander “Skip” Spence. His follow up was arguably even better: 1971's dark, angular masterpiece Time of the Last Persecution, which featured a rawer, electric-rock sound and a stark cover photo of a somber, bearded Fay which eventually contributed to its eventual labeling as a lost, “outsider folk” classic.

Over the years Fay's artistic legacy has been quietly celebrated by contemporary musicians as varied as Wilco's Jeff Tweedy and Current 93's David Tibet. Despite his post-Persecution releases receiving even less attention than their predecessors, he has managed to keep a rather informal career afloat, re-releasing old records and putting out collections of unreleased demos and outtakes on independent labels Coptic Cat and Wooden Hill. This year, however, Fay truly returned to the scene with his first proper studio album in several decades. Life Is People was released in August on Dead Oceans Records to an overwhelming amount of critical attention, and has finally helped bring Fay out of the proverbial shadows.

AD spoke with Fay just prior to the record's release, and found him to be a warm, amiable man far removed from the dark and twisted mythological figure that has been built up around him since the release of Time of the Last Persecution. Misinformation seems to be the name of the game when it comes to discussing Fay's career, and before the interview began, he remarked that he had a bone to pick with some of the music press' coverage of his career:

“Just recently the music press are kind of referring to [Life Is People] as the first studio album in forty years and that doesn't come across as too fair to me, or to the fact that it should be thirty years, because I worked with a group of musicians called the Acme Quartet for about for or fives years which culminated in a studio album called Tomorrow Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Although they included demos in the middle of the album, it was a finished album, and I sent about twelve cassettes out to twelve companies at the time, about thirty years ago. So to me it stands alongside the first two albums and this one, really. It's not fair to them that they could read these things and think “oh, we were there a long time and then we release the album and it kind of doesn't count”.

Aquarium Drunkard: So on that note how would you feel about Still Some Light?

Bill Fay: I'm okay with it because it's not a studio album, so I'm okay with that not counting. And I'm okay with Grandfather Clock, which was a collection of demos and different things. I'm okay with that not counting. The fact that we did put in a lot of work in the late seventies and early eighties and achieved Tomorrow, Tomorrow, Tomorrow — that's the main one. It doesn't read good, in one sense. It should be first studio album for thirty years, although we weren't affiliated to a company. You know, we didn't have a label, we were just kind of recording anyways. So in that sense, this is the first “label” album in forty years, but it's not the first studio album.

AD: Your music has a unique and individualistic sound. I was wondering what some of your first influences were and what led you to develop the sound that you have.

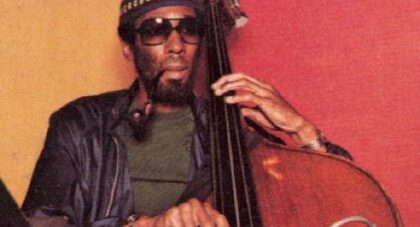

Bill Fay: I think the influence probably comes from all kinds of quarters. I don't there was was any main influence. The piano itself was the biggest influence. It kind of taught me things, like I discovered chords and different things over a certain period of time from the piano itself. So musically I would put the piano as the biggest influence, musically. And then you touch on all sorts of moods, you've heard all sorts of moods from the writing or whatever. But in terms of the Decca records, then — well, if you take the second album first, then the contributions from Ray Russell, Alan Rushton, Darryl Runswick, who played together before I ever linked up with them. Ray played electric guitar on the first album but he had his own music ensemble, so to speak, the urgency of which was totally compatible with the songs that were on the second album. Then the first album, the songs obviously had the arranger Mike Gibbs and I didn't have any say in the kinds of arrangements. But then once again what mike did arrangement wise was very compatible with the songs. I wouldn't say there was a predominate influence in the early years, they're kind of things that you find and they can touch on different moods.

Only the good shit. Aquarium Drunkard is powered by its patrons. Keep the servers humming and help us continue doing it by pledging your support.

To continue reading, become a member or log in.